One of the most interesting things I like to do with the names I have in my database is to trace the life and fates of each individual. By doing this I realize that some of those individuals experienced a lot in different places around the world.

I decided to follow in the footsteps of the Swedish born soldier Alfred Lofdahl. Alfred was born as Johan Alfred Löfdahl in Själevad parish in Örnsköldsvik, Sweden, November 17th, 1878. He grew up in Umeå together with his parents and his six siblings.

He was raised by his parents, his mother Anna Beata Löfqvist and his father Alfred Johan Samuel Löfdahl.

It has been a bit difficult to find the correct date of birth, but in the book of birth it is noted that he was born November 17th, but in some other church books it is noted that he was born November 7th.

In the Swedish church books I find information about that Alfred joined Umeå Naval Corps in 1899, and became a sailor.

In the church books it is noted that he is absent from the Swedish locations from year 1902-1904. This correlates with information that I have found about his activities in South Africa, where he served in Prince Alfred’s Volunteer Guard. During this duty he received The South Africa Medal and clasp (Cape Colony) issued April 1st, 1901.

Probably Alfred stepped off in South Africa during his service as a sailor and in some way contributed to the activities. About the last days of December 1900 a party of about 60 of the corps were in a train which was derailed in Cape Colony. They promptly got out, and fired till their ammunition was exhausted; two were killed and about five were wounded. Alfred could have been among those soldiers who were active during this event.

Alfred later left South Africa and continued to Australia. He arrived to the port of Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, in May, 1906, and by that time he lived on Bonds Road, Punchbowl, Canterbury, Sydney, in New South Wales, Australia. He lived there with his wife Mary Ann Lofdahl and their three children. Alfred applied for naturalisation in January 1916.

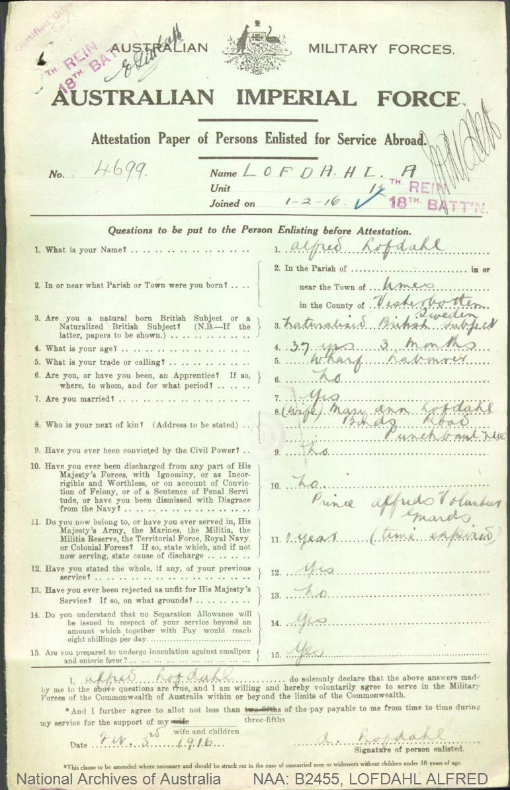

Alfred worked as a Wharf Laborer and something made him apply for the Australian Imperial Forces, AIF, in February, 1916. In those papers he states his correct date of birth, November 17th, 1878.

Alfred was posted to “C” Company, 18th Battalion on 3rd February, 1916 for recruit training. He was transferred to “D” Company of 18th Battalion on 10th February, 1916, then “B” Company on 9th March, 1916. He was transferred to 12th Reinforcements of 18th Battalion on 21st March, 1917.

Alfred proceeded overseas to France on 5th September, 1916 from 5th Training Battalion in England. He was marched in from England Etaples, France on 6th September, 1916. Alfred joined 118th Battalion in the field on 14th September, 1916 from 12th Reinforcements. Alfred was sent sick to Hospital on November 21st, 1916 and then transferred and admitted to 6th General Hospital at Rouen, France, on November 25th. He suffered from Trench Feet and was transferred to England on December 4th, 1916.

He later on marched in to No. 4 Command Depot at Wareham, Dorset, on January 31st, 1917 from Perham Downs. He was transferred from 18th Battalion to 61st Battalion on March 23rd, 1917, and later on taken on strength of 61st Battalion on March 23rd, 1917.

Sadly Alfred died on Wareham Military hospital at Worgret Camp in Wareham of Rapture of “anumpare haemopericordium”, May 11th, 1917, in some kind of life threatening rapture of organs close to heart, or caused by blood in the heart sack.

Alfred was a huge loss to his family, still far away from England, back home in Australia. It is emotional to read the texts from the Australian Newspapers.

Alfred is today buried at Wareham Cemetery, Dorset, England, among 48 other WW1 burials.

Imagine the trip Alfred did, from Sweden, South Africa, Australia, and then back to Europe to participate in the Great War, to finally die of Illness, after have experienced the war within the Australian units.

Alfred’s son, Eric Samuel Lofdahl, went in his father’s footsteps, and participated in WW2. He served on the Island of Marotai of a period of around 9 months. I haven’t found any photo of Alfred, but maybe there is some resemblance of Alfred in Eric?

I will continue to inform my Swedish fellow citizens about what some of them experienced during the period of the Great War, as this is close to my heart. May Alfred rest in Peace.